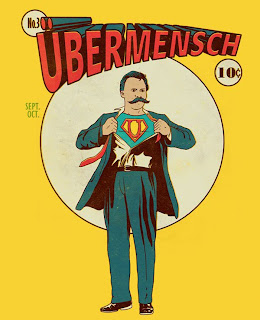

So, I've been reading this H.G. Wells book. Most people assume it's one of the classics. But to be honest, like everyone else I've talked to so far, I had never heard of "Star-Begotten," released in 1937. I shouldn't be surprised, really, that this text discusses the some of the more philosophical points of religion and Nietzsche's Superman. 'Why not?,' you ask. Well, H.G. Wells was friends with that whole cliquey of philosophically pondering fantasy sci-fi writers from the early 1900's = C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, E.R.R. Eddison, (geeze dudes: what's with all the initials?) Olaf Stapledon, and others. So here I am, getting towards the end of the book, and I come upon the following passages:

as they grew up they will have found themselves mentally out of key. They will have found a disc[on]certing inconsistency about things in general. They will have thought at first that the abnormality was on the side of particular people about them and not on their own.

They

Theywill have found themselves doubting whether their parents and teachers could possibly believe what they were saying. I think that among these Martians, that odd doubt - which many children nowadays certainly have - whether the whole world isn't some queer sort of put-up job and that it will all turn out differently presently - I think that streak of doubt would be an almost inevitable characteristic of them all"

'You spoke just now of stale religion,' he went on. 'Such a lot of

things in life now are stale. Out of date.... I agree....'

He felt his way forward with his argument. 'I suppose--I suppose all the

main working ideas that have held people together in communities have

been getting out of date pretty rapidly in the last hundred years.

Strange new influences have been at work--as we three at least are

beginning to understand. But because human society is a going concern,

the main working ideas have never been replaced. There never came a

definite time to replace them. They have been used in new senses, made

ambiguous, expanded, attenuated. Replacement was something too heroic

altogether. But each time there was a patch-up there had to be fresh

strains and fresh distortions. Old things got used for new purposes, and

they did not stand the wear. So that--what shall I call it?--the social

ideology--the social ideology has become a terrific accumulation of old

clutter which now, simply through the wear and tear of terms misused,

has come to mean anything or nothing. And to work less and less surely

and safely.... Do I make myself plain, Keppel?'

'There is this secondary world which has worked its way into the

language everywhere, a sort of fold in the membrane that has established

itself in a thousand metaphors, got itself most unwarrantably taken for

granted by nearly everybody. Other worldliness, the idea of a ghost

world, a spirit world, side by side with actuality. It overlaps and lies

beside reality, like it and yet different; a parody of it done in

phantoms; a sort of fuddled overlap; a universe of imaginary emanations,

the consequence of congenital squint. Beside every man we see his

spirit--which is not really there--beside the universe we imagine a

Great Spirit. Whenever the mental going is a bit hard, whenever our

intellectual eyes feel the glare of truth, we lose focus and slither off

into Ghostland. Ghostland is halfway to dreamland, where all rational checks are lost. In Ghostland, that world of the spirit, you can find unlimited justifications for your impulses; unlimited evasions from rational obligation. That’s my main charge against the human mind; this persistent confusing dualism. The last achievement of the human mind is to see life simply and see it whole.'

'You spoke just now of stale religion,' he went on. 'Such a lot of

things in life now are stale. Out of date.... I agree....'

He felt his way forward with his argument. 'I suppose--I suppose all the main working ideas that have held people together in communities have been getting out of date pretty rapidly in the last hundred years.

Strange new influences have been at work--as we three at least are

beginning to understand. But because human society is a going concern,

the main working ideas have never been replaced. There never came a

definite time to replace them. They have been used in new senses, made

ambiguous, expanded, attenuated. Replacement was something too heroic

altogether. But each time there was a patch-up there had to be fresh

strains and fresh distortions. Old things got used for new purposes, and

they did not stand the wear. So that--what shall I call it?--the social

ideology--the social ideology has become a terrific accumulation of old

clutter which now, simply through the wear and tear of terms misused,

has come to mean anything or nothing. And to work less and less surely

and safely.... Do I make myself plain, Keppel?'

things in life now are stale. Out of date.... I agree....'

He felt his way forward with his argument. 'I suppose--I suppose all the main working ideas that have held people together in communities have been getting out of date pretty rapidly in the last hundred years.

Strange new influences have been at work--as we three at least are

beginning to understand. But because human society is a going concern,

the main working ideas have never been replaced. There never came a

definite time to replace them. They have been used in new senses, made

ambiguous, expanded, attenuated. Replacement was something too heroic

altogether. But each time there was a patch-up there had to be fresh

strains and fresh distortions. Old things got used for new purposes, and

they did not stand the wear. So that--what shall I call it?--the social

ideology--the social ideology has become a terrific accumulation of old

clutter which now, simply through the wear and tear of terms misused,

has come to mean anything or nothing. And to work less and less surely

and safely.... Do I make myself plain, Keppel?'

'There is this secondary world which has worked its way into the

language everywhere, a sort of fold in the membrane that has established

itself in a thousand metaphors, got itself most unwarrantably taken for

granted by nearly everybody. Other worldliness, the idea of a ghost

world, a spirit world, side by side with actuality. It overlaps and lies

beside reality, like it and yet different; a parody of it done in

phantoms; a sort of fuddled overlap; a universe of imaginary emanations,

the consequence of congenital squint. Beside every man we see his

spirit--which is not really there--beside the universe we imagine a

Great Spirit. Whenever the mental going is a bit hard, whenever our

intellectual eyes feel the glare of truth, we lose focus and slither off

into Ghostland. Ghostland is halfway to dreamland, where all rational

checks are lost. In Ghostland, that world of the spirit, you can find

unlimited justifications for your impulses; unlimited evasions from

rational obligation. That’s my main charge against the human mind; this

persistent confusing dualism. The last achievement of the human mind is

to see life simply and see it whole,'

138

'The creature hardly ever becomes adult. Hardly any of us grow up

fully. Particularly do we dread and shirk complete personal

responsibility--which is what being adult means. Man is the boy who

won't grow up, but he grows monstrous clumsy and heavy at times all the

same, a Goering monster, a Mussolini--the bouncing boys of Europe. Most

of us to the very end of our lives are obsessed by infantile cravings

for protection and direction, and out of these cravings come all these

impulses towards slavish subjection to gods, kings, leaders, heroes,

bosses, mystical personifications like the People, My Country Right or

Wrong, the Church, the Party, the Masses, the Proletariat. Our

imaginations hang on to some such Big Brother idea almost to the end. We

will accept almost any self-abasement rather than step out of the crowd

and be full-grown individuals. And like all cubs and puppies and larval

things, we are full of fear. What is the Sense of Sin but the

instinctive fear of an immature animal? Oh, we are doing wrong! We are

going to be punished for it! We are full of fears, fears of primal

curses and mystical sin, masochistic impulses to sacrifice and

propitiate and kneel and crawl. It paralyses our happiest impulses. It

fills our world with mean, cruel, and crazy acts.

'And what isn't purely infantile in us is at best early adolescent. Our

excess of egotism! We all have it. It is a commonplace to say man is as

over-sexed as a cageful of monkeys, but sex is only one manifestation of

his stupendous egotism. In every respect he is insanely

self-centred--beyond any biological need. No animal, not even a dog, has

the acute self-consciousness, the incessant, sore, personal jealousy of

a human being. Fear is linked to this--there is no clear boundary

here--and so is the hoarding instinct. The love of property for its own

sake comes straight out of fear. This terrified, immature thing wants to

be safe, invincibly safe, and so, by the most natural transition, fear

develops into the craving for possessions and the craving for power.

From the escape defensive to the aggressive defensive is a step. He not

only fears other beings, he hates them, he flies at them. He fights

needlessly. He is cruel. He loves to conquer. He loves to persecute....

Man! What was it Swift said? That such a creature should deal in

pride!'

'Homo superbus, eh?' said the doctor. 'But listen, Keppel. Is he

really so bad as all this? Just a scared, self-defensive, immature beast

squinting at the world because he has never yet learned to look

straight? And hopeless at that? You experimental psychologists have been

cleaning up our ideas about the human mind very fast in the past thirty

or forty years. Very fast. You have been making this damaging--well, this

salutary--analysis of our motives and errors--our queer little ways.

Yes.... You couldn't have said a word of this forty years ago.... In my

profession we say a sound diagnosis is halfway to a cure. Indicating

the human mind is like sending a patient to bed for treatment. Maybe the

treatment begins at that.'

'Well?' said Keppel.

'Isn't the time almost ripe for a new education that would clear the stuff from the creature's eyes, stiffen his backbone, teach him to think

straight and grow up? Make a man of him at last?'

Davis shook his head. He spoke rather to himself than to the others. 'Man is what we've got. Humanity is humanity. Starry souls are born not

made.'

We are living--let us face the facts--in a lunatic asylum crowded with patients prevented from knowledge and afraid to go sane.' (128-147)

Now, the Superman was an important and interesting topic of discussion for Needleman's 'Transformative Lecture,' course, so I found the book very interesting. I did some basic searches, but it has been hard to find a plethora of knowledge of H.G. Wells' religious beliefs. At least not that I believe....There were a few wacky conspiracy pages on Wells as a crazy eugenicist. And a few nutty Christian pages on Wells as a godless boogie man. But really, I guess I just need to read some of his other texts, like "God The Invisible King," and figure it out for myself.

It's so interesting to me that these philosophical religious concepts have arisen again and again throughout history. It may be, as Richard Dawkins would argue, an inevitable function of our genetics and evolution, but I don't really care. All I see is the outline of a path that has been walked by many prestigious thinkers before me. And I might as well

use what my ancestors have given me (no booty shaking though, thank you...okay, just a little...). So I hope to learn what they have learned and take a walk. I'm not sure where it will lead me, or if it has an end on which I might build myself. But I've always been a walker myself.

use what my ancestors have given me (no booty shaking though, thank you...okay, just a little...). So I hope to learn what they have learned and take a walk. I'm not sure where it will lead me, or if it has an end on which I might build myself. But I've always been a walker myself.Peace and Love,

Tesla

No comments:

Post a Comment